Why Monuments Matter — An Opportunity to Visually Define an Ever Evolving America [Part 1]

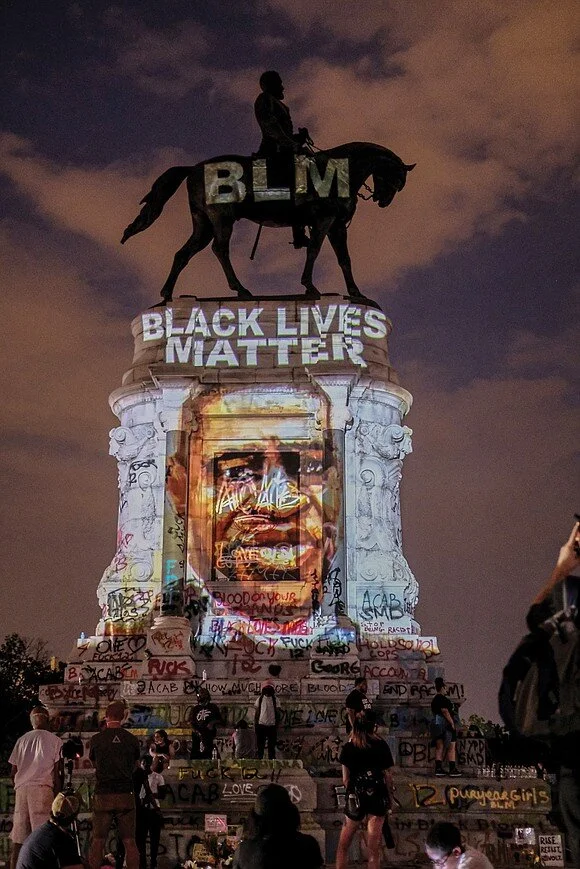

Black Lives Matter protesters gather around Robert E. Lee statue in Richmond, Virginia, June 2020. Image Credit: Daniel Sangjib, MIN/RTD.

On a summer evening, a crowd of New Yorkers gathered to hear an impassioned speaker read a new document aloud. He condemned “a history of repeated infamies” and a government of “absolute tyranny.” He stressed that “Our repeated Petitions have been answered by only repeated injury,” and spoke of him, and how he is “unfit to be the ruler of free people.” With every line read, the crowd’s agreement became more audible. The discontentment had been mounting for some time and change was the only solution now that the truth had been proclaimed. Full of zeal and disillusioned with peaceful protest, they marched in anger and with determination down to the square. They hopped the fence and, with ropes in hand, lassoed the monumental equestrian statue. They cheered and pulled tight, and within a few short moments the bronze sculpture cracked off it’s high pedestal and crashed to the ground below, fracturing into pieces.

No, this is not a description of a protest from today’s Black Lives Matter movement (as pictured above) or from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, but of another act of patriotic vandalism from America’s early revolutionary days, as reimagined in Johannes Adam Simon Oertel’s painting of Pulling Down the Statue Of King George III, New York City, 1852-53. After hearing The Declaration of Independence — the segments quoted above — read for the first time aloud, the colonists decided they would answer to this king no more and in a symbolic gesture for how they felt about his reign, desecrated the king’s image that represented his royal authority. A colonist newspaper wrote of the event,

“The equestrian statue of George III which Tory pride and folly raised in the year 1770, was by the sons of freedom, laid prostrate in the dirt the just desert of an ungrateful tyrant!”

Johannes Adam Simon Oertel, Pulling Down the Statue Of King George III, New York City, 1852-53, Oil on canvas, 32 x 41 ¼ inches, Collection of The New-York Historical Society.

By July 17, 1776 the people had decided that King George III was no longer a symbol to be revered and respected in the colonies. (Truth be told they were not too keen about the sculpture when it was erected six years earlier.) His image and all symbols relating to his reign became the visual antithesis for freedom, equality, and liberty. Instead, he represented the very “Oppressions” that were listed in our Declaration. So, his image was removed. These rebel colonists had begun the process of redefining themselves and their values — they were becoming Americans.

What does it mean to be an American?

The term American (in italics) is used here in its idyllic, mythological definition, whereby it is synonymous with the struggle for independence and equality, by any means necessary. The forming of this country’s ideals and laws, through the United States Constitution, laid an attractive foundation, and, most importantly, left room for improvement through amendments— it is a living document. Similarly, being an actual American and living up to an American exceptionalism standard, is ever-evolving —complicated at its best and horrific at its worst. In its infancy, being an American was a highly exclusionary concept. The privledge was reserved only for property-owning white men born in the colonies, whose patrichal views, accepted the brutality of slavery and colonialist ideals of forcefully taking land from surrounding nations. Women, indigenous peoples, all people of color, immigrants, and LGBTQ communities were not considered and were, in fact, actively excluded by means of force and in many instances death. This did not dissuade these excluded groups or their allies from demanding to be included by quoting//repeating back the very words the founder’s wrote.

It has taken over two centuries of slow, painful conflicts, a revolutionary mindset and minor victories, including: a civil war, numerous treaties created and broken, the Jim Crow laws, constitutional amendments, suffragist movements, and civil rights protests to come only to where we are today. This fight for true equality continues — the very ideal and mythology that being American stands for— has been a relay race, fraught with obstacles, passed from generation to generation. It has always been one step forward and three steps backward.

Now two-hundred and forty-four years after our founding, we’ve embraced our rebellious American roots, to challenge the state of current systems. And once again persistent petitions to our leaders —this time elected —were only answered with injury and even death at the hands of those who were sworn to serve and protect citizens like George Floyd (among too many others ). So the people of this republic took to the streets and in a series of Declarations, demanded equality, liberty and justice by distilling it to a sole phrase: Black Lives Matter, a bold reminder to those who have forsaken, neglected and actively rejected the right’s of those who are Black. And, once again protestors decided that all symbols that represented these systemic inequities — especially those of “Lost Cause” slave-owning generals— be destroyed, removed or recontextualized. In acts of patriotic vandalism they hopped the fences and grabbed the ropes and desecrated the very symbols that stood for knees on their necks. These “Good Trouble” citizens (a phrase the late activist, Congressman John Lewis coined) had begun the process of redefining their society and reevaluating their values —- they were simply being Americans. Now “equality for all” needs to mean equality for all and this generation seems intent on fulfilling that promise penned long ago.

Revolution, it appears, is a part of our collective consciousness as Americans — we are not afraid to overthrow a system of social order or even government that has ceased to work for us or worse, has actively oppressed a group of citizens. It is instructive to see that in these instances the immediate need to tear down the physical symbol of the system that the public (or a portion of the public) abhors was the tipping point for actual change in our national identity — from colonists to Americans. As art historian Erin L. Thompson summarizes,

“Throughout history, destroying an image has been felt as attacking the person represented in that image. Which we know because when people attack statues, they attack the parts that would be vulnerable on a human being. We see ancient Roman statues with the eyes gouged out or the ears cut off. It’s a very satisfying way of attacking an idea — not just by rejecting but humiliating it. ”

The act of iconoclasm, as it has since our founding, grabs the country’s attention. These performances of ‘patriotic vandalism’ provoke us and become the impetus for conversation. We are forced to think about ourselves and our identity in relation to these art objects.

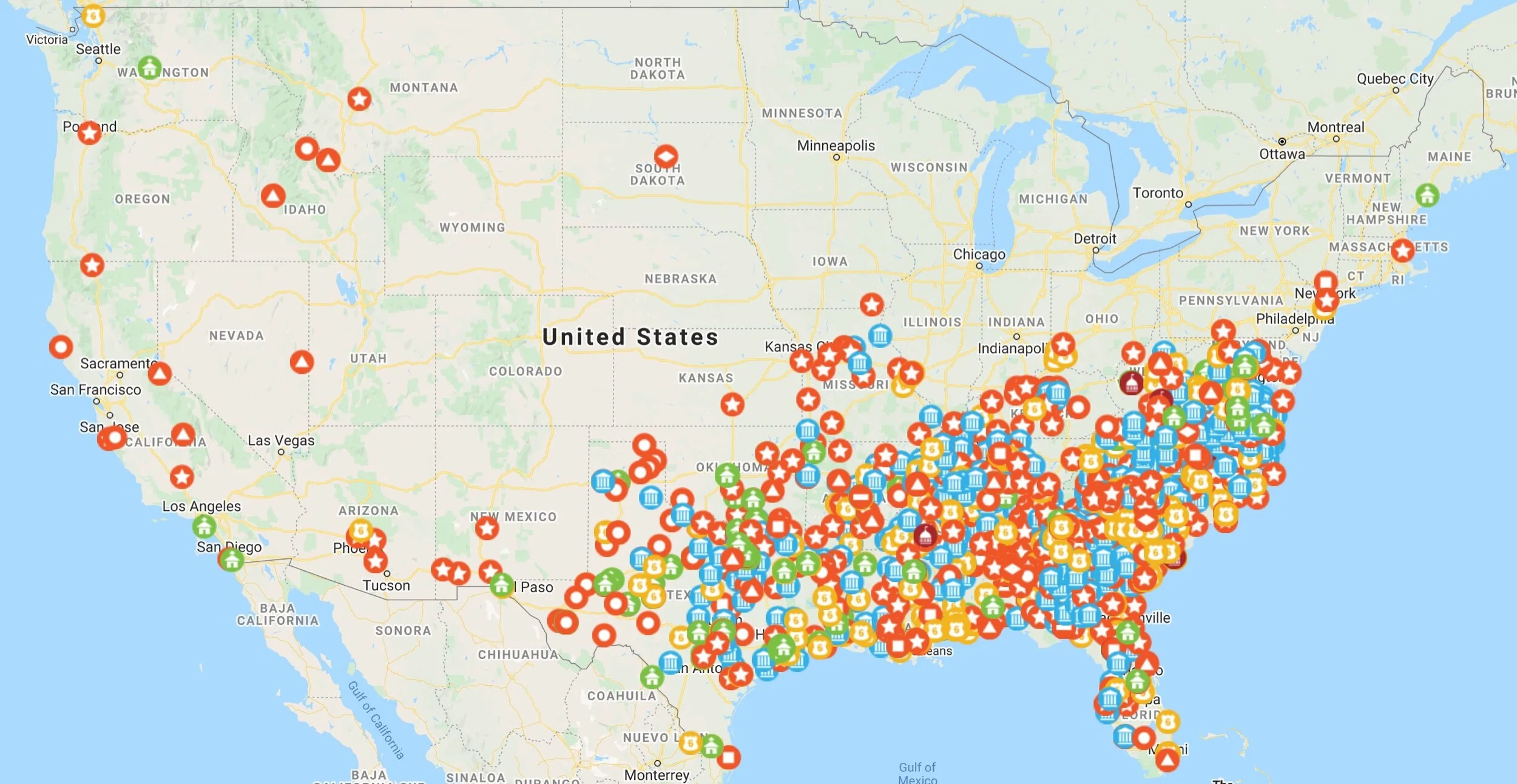

Most recently, there has been an increased focus to remove monuments that honor the late Confederacy and its “Lost Cause.” Close to two thousand of these statues and memorials went up across the south beginning in the Jim Crow era and through the mid-twentieth century, with a goal to “keep public space white.” Luckily, the shift in public opinion from only 39% approving of their removal in 2017 has now tilted to the majority at 52% in 2020. Today the Southern Poverty Law Center monitors the fate of these toxic Confederate symbols using Whose Heritage?, an interactive data set and map. Fortunately, since May 2020, one-hundred-and-two have been pulled down by protestors or removed by local government.

Map of Confederate Monument or Symbols located throughout the United States. Source: Southern Poverty Law Center/Google Maps

These actions pose a critical question to those communities who continue to house them: What does a sculpture of a Confederate General like Robert E. Lee mean to you? And as we hear more individuals chime in with their thoughts and concerns from all sides, a conversation begins. In the best-case scenario, these acts challenge individuals to think deeper and consider what these public works of art might mean to others, to our community and to the country as a whole, rather than simply what it means to ourselves. In his speech, Mayor Mitch Landrieu explains why the city of New Orleans was removing its Confederate sculptures,

“Another friend asked me to consider these four monuments from the perspective of an African American mother or father trying to explain to their fifth-grade daughter who Robert E. Lee is and why he stands atop of our beautiful city. Can you do it? Can you look into that young girl’s eyes and convince her that Robert E. Lee is there to encourage her? Do you think she will feel inspired and hopeful by that story? Do these monuments help her see a future with limitless potential? Have you ever thought that if her potential is limited, yours and mine are, too?”

The City of New Orleans prepares for the removal of Robert E. Lee Monument. Image Credit: NPR.org

The movement has also amplified discussions about other — now glaring— issues in our public art. There have been calls across the nation to address monuments that perpetuate oppression and racism towards Indigenous Americans such as the ubiquitous presence of Christopher Columbus. By late September, thirty-three statues of the explorer were removed. The debate, however, continues as many, including New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, believe the statue to Christopher Columbus in Manhattan’s Columbus Circle should remain:

“I understand the feelings about Christopher Columbus and some of his acts, which nobody would support. But the statue has come to represent and signify appreciation for the Italian American contribution to New York. For that reason, I support it.”

Our national dialogue is also exposing the sheer lack of representation honoring the deeds of minorities, who are represented in only a fraction of the monuments but make-up nearly 40% of the population. The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation hopes to change this with its $250 million ‘Monument Project,’ as their president Elizabeth Alexander stated, “There are so many stories of who we are that need to be told. We don’t have our actual, true history represented in our landscape.”

Another abysmal oversight is the representation of women in our monuments — less than 10% honor women nationwide according to the Smithsonian Institute. It was not until August 2020 when Central Park in New York City welcomed its first monument honoring real (and not fictional) women in its one-hundred and sixty-four year history, Meredith Bergmann’s Women’s Rights Pioneers, 2020. Now only five sculptures of historic women stand in all of New York City with plans to add a sixth to honor the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg in Brooklyn.

Meredith Bergmann, Women’s Rights Pioneers, 2020, Bronze, Collection of Central Park, NYC.

It is imperative that we use our statues, sculptures, public art and memorials as tools to define, solidify and capture our national identity. The events we chose to memorialize, the individuals we decide to place on pedestals and the very sites we deem to have historic value matter. They provide the immortal propaganda for reinforcing our belief systems and if you look around at not only who is represented, but how they are represented, issues with seemingly innocuous sculptures start to arise.

Take, for instance, James Earle Fraiser’s Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt, 1939.

James Earle Fraiser, Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt, 1939, Bronze, Collection of The American Museum of Natural History and the City of New York.

This massive bronze equestrian statue was originally situated on the grand staircase entrance to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). It honors the legacy of former President Theodore Roosevelt, a New Yorker, naturalist and conservationist. Roosevelt sits high in the saddle, his posture erect, and faces forward, staring directly and purposefully ahead. He holds the reins securely in his left hand, leaving his right hand free, hovering over the holster and always at-the-ready. His dress is casual, rather than presidential or military, donning a form- fitting, long-sleeved shirt rolled up above the elbow and snug trousers secured with a cartridge belt completing the ultra-masculine persona look. Flanking him on either side, on foot, are two standing male figures. On his right, an Indigenous American wearing an elegant full headdress, with a toga-like garment draped over his shoulder revealing his muscular torso and arms. On his left, a mostly nude African man with an equally idealized physique, drapes a long blanket or cloth over his right shoulder. Both figures hold rifles against their shoulders closest to the horse, perhaps implying that they are his hired hunting guides. And both men stare straight ahead, with a vacant expression and slight stride forward.

Detail views of the Indigenous American and African allegorical figures.

The debate of this monument is primarily centered around the two male figures of the Indigenous American and African. There are those who believe that these figures are purely allegorical representation of the continents of Africa and America, as explained by the artist in 1940, versus those who see the grouping as a divisive racial hierarchy, especially in light of both Roosevelt’s problematic views on race and the AMNH’s prior interest in eugenics. In 2017, the Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments and Markers discussed issues of public art on New York City owned land, including the Roosevelt monument. Regretfully, they were unable to reach a consensus on the statue’s fate, with the group divided with approximately half advocating for “additional historical research,” the other half believing the work should be relocated (but disagreed on where) and a handful of commissioners advocating to keep the work in-situ, but “provide additional context on-site.” By 2019, the AMNH opened Addressing the Statue, an exhibition that provided a more complete history and dialogue around issues of race. However, by June 2020 and directly following murder of George Floyd, the AMNH announced,

“While the Statue is owned by the City, the Museum recognizes the importance of taking a position at this time. We believe that the Statue should no longer remain and have requested that it be moved.”

For argument’s sake, even if this sculpture was meant to depict unity among races when it was erected, the simple fact remains that is not the contemporary interpretation when you include the perspectives of Black and Indigenous New Yorkers. We must also consider the placement of this work at the entrance to a major museum where education is paramount and that there are a great deal of children who would be seeing this as a racial hierarchy with their contemporary eyes. To paraphrase Mayor Landiau, “Can you look into these children's eyes and convince them that this sculpture is there to encourage them? If they are only represented as, at best, sidekicks, or worse, racially inferior? This is why the stakes are higher for art that is on public view; we need to make sure we include and be sensitive to multiple perspectives as each work should be representative of our values and community. Perhaps we should all heed Roosevelt’s advice,

“Knowing what’s right doesn’t mean much unless you do what’s right.”

We know we can do better, and we should.

This self-realization or “wokeness” also serves as a cautionary tale for how we should consider building monuments going forward. These lessons should challenge us to be more sensitive to how future generations may perceive our choices of individuals to honor or events to memorialize. As a democratic nation, we seem to place a large value on our military generals and politicians (who happen to be both white and male), as evident in their over-representation compared to other history-worthy accomplishments — is this representative of our nation? We may also look to public artworks that still provide inspiration like the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, DC. The interwoven connection between identity, memory, written history and visual monument provides us with critical context to weigh before constructing new monuments, memorials and public art.

As Americans, we seem to be grappling with our national identity due to a myriad of issues including extreme bi-partisanship, systemic racism, and wealth inequality. Just as therapeutic and symbolic, collectively-removing a statue can be for joining a community, the reverse can also be true. Our public art could be used as a great unifier by both putting our values on display and acknowledging our troubled past.

“Art is restoration: the idea is to repair the damages that are inflicted in life, to make something that is fragmented – which is what fear and anxiety do to a person – into something whole.”

Monuments, Memorials, public art and historic sites— whether we agree with their content or not —are the visual representations of “our” public values and systems, becoming the “avatars of civic virtue.” They populate public shared spaces in our communities and the majority are maintained — at great expense —by our tax dollars. They are typically large or oversized, being made of durable bronze or stone, while their very material emits a permanence and immortal-like status for their subject. They look down upon the viewer from “pedestals,” physical pillars to be admired from below. They continue a long tradition of the Western art canon that places those who are God-like “on pedestals” to be worshiped and revered; or as places of worship or contemplation or sacred space. The visual language is baked-in to our consciousness and we perceive these artworks and their spaces as important to our national identity, even if they are exclusionary, misleading or outright fictional.

This is why monuments matter.

Author’s Note:

Over the course of this year, I will continue to post chapters of this article. I intend to address why monuments are actually worth discussing when so much systemic change needs to occur, and to also narrow in on the framework we must put in place for creating future public art responsibly and inclusively. It is a conversation we must all have together, as an art community and as a nation.